Where to start?

I don’t mean this blog post, but literally, with game development, where do I start?

Well this has been something of an uncomfortable conundrum for me, because, my skill set is not well rounded at all. In some areas I’m very strong and in others very weak, and deciding exactly where to begin on this game development journey is therefore a case of taking my skills into account, and deciding where to apply my energy. A problem that I’ve struggled with in one form or another for my entire life.

The Game Engine

If I’m an expert at anything at all in this life, it’s programming. As I mentioned in my introduction post, I was given a programmable computer at just five years old. I began copying programs from the user manual, and altering them to learn how things worked. I don’t think there has been more than a single consecutive week since, that I’ve not had a computer in front of me at some time in the day. It’s my thing, and depending on the choice of tool-set, I’m quite good at it. In fact, I’d claim to be TOO good at it, something of a perfectionist, and this lead me to my first conundrum…

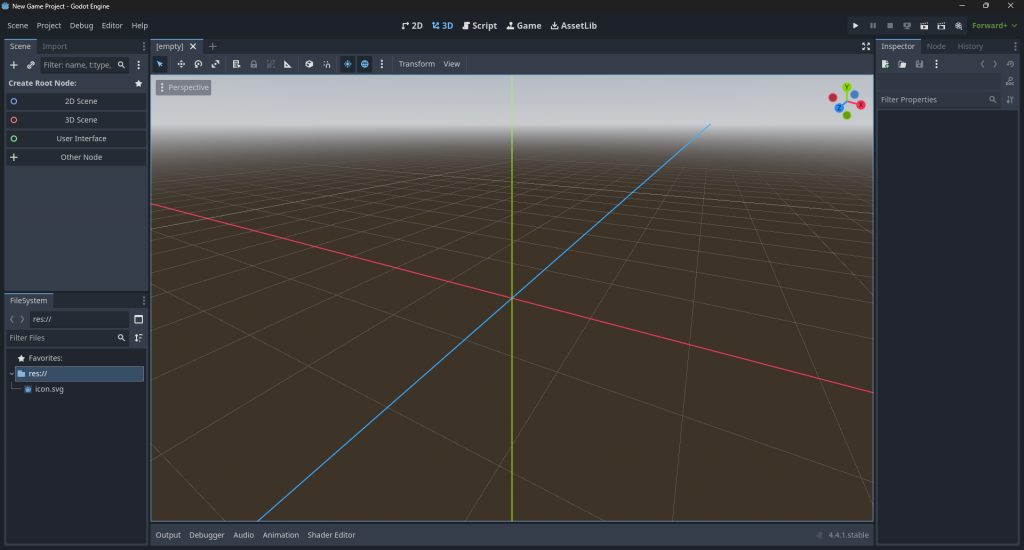

When I look at the available game engines for Indie developers, the three biggest names are Unreal, Unity and Godot. Each of these engines is a powerhouse in their respective use case, but all three of them have issues which, as a “perfectionist programmer” trouble me. I look at how they function and things bother me, from OOP based hot loops, to inefficient lookup, to black-box threading models and so on. These issues troubled me so much that I decided I might just build my own Game Engine using my programming language of preference. No, not C or C++ but Pascal. So I made a start on it…

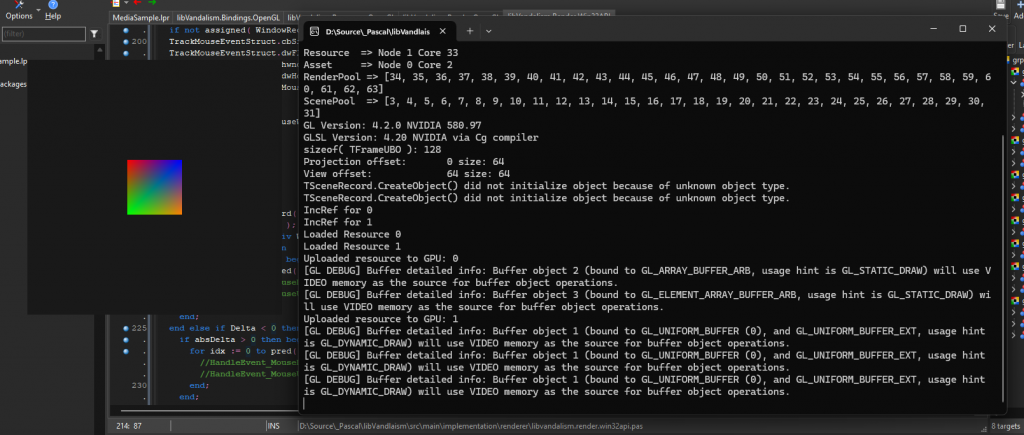

What you’re seeing in the screen shot is quite unimpressive looking, it’s rendering a “rainbow plane” in my own custom game engine. It’s actually far more impressive than it looks. I wrote an entire runtime library with a custom, thread affinity and numa aware heap allocator, various collection allocators, and its cross platform. This engine supports an OpenGL based renderer on Windows and Linux, including Aarch64 ARM. It handles windowing on Windows and X-Server with gaps to plug in Wayland and dummy window managers for Android and iOS. It has space to plug in alternative rendering API’s to use Vulkan, Metal / other. It is entirely procedural code and data-oriented, with numa locality of memory, a fabric layer to orchestrate multi-threading, a dedicated thread for rendering, another for scene simulation, and thread-pools for array-slice based cache locality. If this is all word salad, let me give you the brief : This engine is engineered in as immaculate a way as I know how, and it took around six months to get to the point that I could render this rainbow box!

(Okay, it actually does more than this – in prototypes I’ve had 50k spinning rainbow cubes on display, in twin windows, without melting the CPU, but that’s a mere aside from my point.)

That’s the problem right there. I have the engineering skills to write a complete Game Engine of my own, and to do a good job of it, at least as I see it, but it’s going to take far too long to get to the point that it’s actually a usable engine. Not only that, but I’ve been driven by this form of insanity for a long time. For instance, the available compilers for Pascal have a limited number of targets, and so I’ve even begun writing my own compiler with a Pascal-based syntax, which is able to target x86-64/Aarch64 with its own encoders written from scratch, its own linker written from scratch. This is a rabbit hole! Simply because I could re-invent software technology from scratch, does not mean that I should!

I considered switching to C or C++ too. You see, another limitation of Pascal is simply that it’s not the compiler that “won” the compiler wars of the 80’s and 90’s. That crown went to C, and by extension to C++. The result is that in order to do something like this in Pascal, you must interact with C based ABI’s and API’s. Doing so requires a capable compiler, and careful translation of header files from C to Pascal. There are some existing headers out there, but they tend to be of poor quality or behind in being maintained because Pascal just hasn’t been as popular a language. I know enough C and C++ to do these translations, but doing them right can take days – and there are a lot of them to do. Consider the engine I’ve described above for example. Just to get that to work, I had to translate the Windows API headers, the Posix headers, OpenGL, X-Server, XInput, Wayland, and there were many more to come, including Vulkan, Metal and so on… not to mention bridging to Android and supporting iOS. If I switched to C++ for my engine, I could save myself this work because those headers not-only already exist for C++, but they are maintained for it, because they’re written in C++ or compatible C.

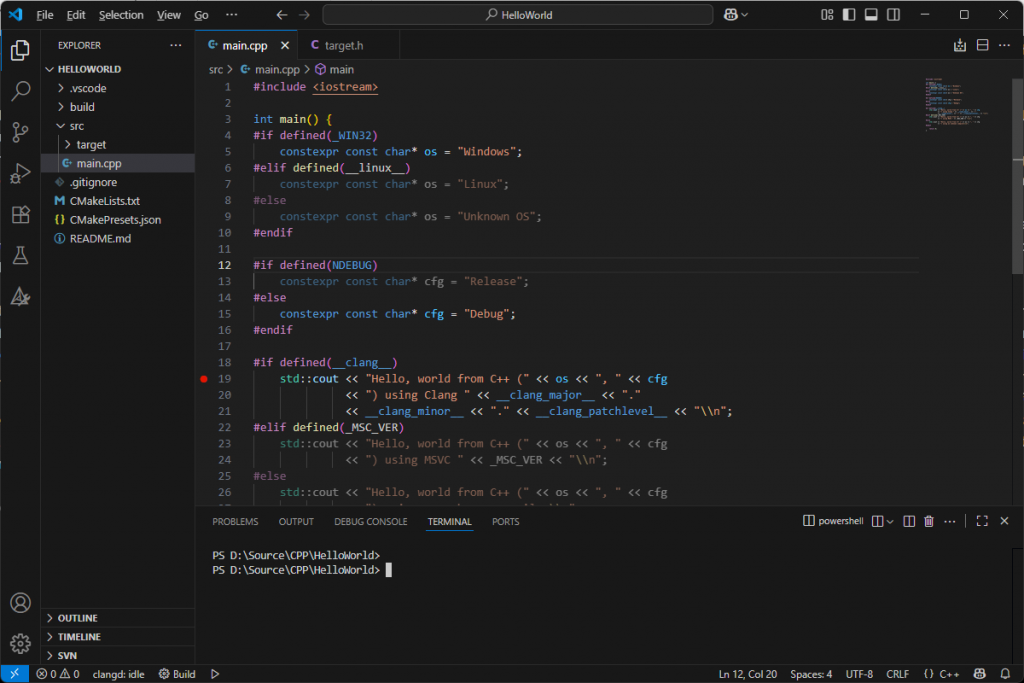

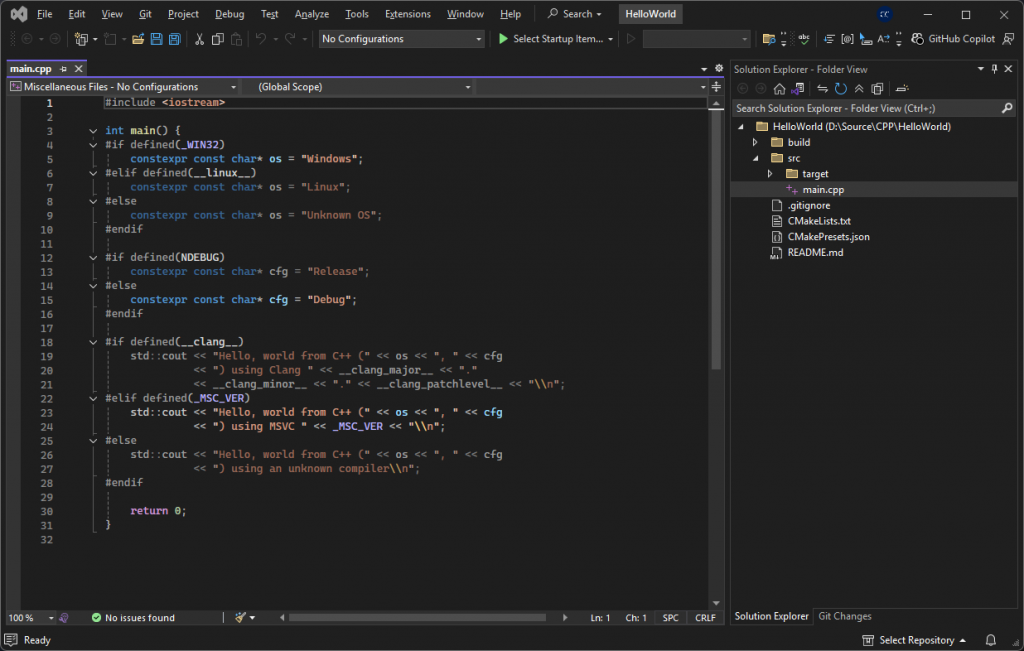

Then I looked at the C and C++ tool-chain space for cross platform development, something I’ve not looked at in many years. The space is dreadful. I’ve been spoiled with Pascal because its unit system allows for modular construction of cross platform code. The compiler takes care of the linking stage, it’s syntax is sufficient that it knows what to link for any given target, and depending on the compiler it either links for its self, or drives an external linker. In order to use C or C++ today, you must first select a compiler, linker and debugger, then select a compatible build system from the many available, then select the runtime you want to link against, then find an IDE or Editor which understands the build system and figure out how to configure the thing. The slickest experience I think is Visual Studio 2022 Community Edition, but, it only runs on Windows and if you’re not using its CMake support it only supports building for windows. So, I considered VS Code – which means adding a handful of plugins and configuring them each to find the compiler, the linker, the build system, the RTL, the SDKs and so on and so on. Starting a new project is not a case of hitting a menu item to create a new project, it’s a matter of carefully crafting build files which litter the source code, just to get something to build and be ready for cross-platform use.

Okay, so. If I take on this task and get through it (as I did, it took some hours to figure out), then I get to a working C++ compiler… and, well, the syntax is just horrible. It has all the nice comfortable features that you might want, if you know the special incantations to use them. In my case, I wanted a procedural programming style as I’d used for my own engine in pascal, because procedural is deterministic in terms of performance, cache friendly, and actually quite pleasant to work in too. It reminds me of those good old days… C is the procedural language, but it lacks a lot of nice features such as namespaces and generics (templates), so I figured, okay, I can use C++ but limit myself to its procedural features. There’s a lot to like, and it does provide most of the features that I’d want, but it’s ugly as sin. C++ is designed by committee, and it shows. It’s a language that feels like every syntax feature has been “bolted on” over time, where-ever there was space. Having specialized around Pascal for both my career and hobby for so long, I’m actually not a little horrified that this is where the C/C++ development world has ended up. Why do people put up with it? Well it seems that they don’t all. There are developers out there that, as I did, decided to write their own compilers to ease the pain, and they are further along that process than I am. More power to them, but continuing that project myself right now is a deep distraction from my goals.

STOP!

So I decided to stop this insane rabbit-holing. I WILL at some point in the future return to building my own compiler and game engine, because that itch is just never going to go away, but as I’ve explained in my introduction post, my goal is to be writing games. This is what I want to be doing with my life. This feels like waking up, like I’ve been sleeping since the 90’s. You see, in the 90’s if you wanted to make video games, more or less, you were going to write a dedicated game engine for each game. I’m from the era in which you first wrote the code to put graphics on the screen, then you wrote the code to control the audio device, then you realized you’d neglected all the red-tape like input and simulation, so you got to work writing those. Games were simpler, and so too was the technology. Using a 3D rendering API would still have been rare, you’d instead write graphics to a linear memory buffer, manually. In the time since then, writing games for modern hardware and using modern API’s has become ever more complex. If you want to write games today, you don’t sit down and write your own engine, or get crazy and write your own compiler…. well, some do, but they clearly have longer time-lines than I do – I want to be writing games now, so it’s time to just select an engine and roll with it.

So lets do a quick evaluation of “the big three.” Unreal engine is incredibly powerful and high fidelity, however, I’m not going to be needing it’s high-end features, at least, not any time soon, so is it worth it? It’s generally considered to be a game engine for first-person games only. Sure it can be used for other types of games, but you’re fighting against what it was built for, and that’s first-person high fidelity. Not only that, but the programming language employed by it is C++, which I can do, but as I’ve already explained, I do not enjoy. So lets count that one out.

So Unity or GoDot? Well this is actually a very simple one to answer, but with a minor complication. GoDot employs a python-like programming language called GDScript, and despite some “Jitting” capabilities, it’s essentially an interpreted language. This is not necessarily a blocker, but in my experimentation with it, I found it’s performance to be quite poor. It does support C# also, but as an extension. GoDot doesn’t target the hot consoles (nintendo / sony etc) due to licensing issues, though its projects can be ported to those consoles. Typically, porting would involve employing a porting company to do the port. Because the porting company have already ported the GoDot engine itself, they can short-cut to porting your games. If you use C# however, it may not be possible to do the port directly, because the consoles don’t generally support the necessary runtime. So, Godot is out for me. I don’t like the programming language, and I don’t like the questions about potentially targeting consoles some day.

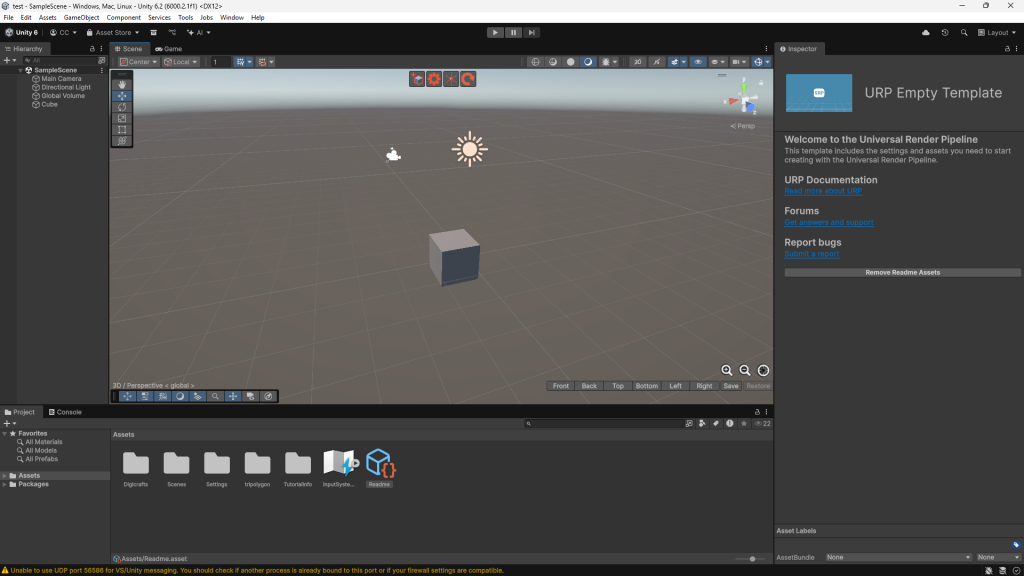

The Unity engine is based around C#. Unlike GoDot when using C# however, when targeting consoles it does something a little clever. It performs ahead of time compilation of the C#, compiling it down to its immediate-language, and then it ports that immediate-language representation to C++ and does a native build. For this reason, the Unity engine is able to support console targets out of the box. You do need to be approved by the target company first, but once you’ve signed all the relevant NDA documents and been approved, Unity will give you the tools to port and deploy your games to consoles yourself.

What about the language C#? Well, frankly, Microsoft may or may not appreciate me saying this, but it’s essentially Pascal with curly braces. You see, the Chief Architect of C# is the very same man that was once the Chief Architect of the Delphi Pascal language. To claim that Pascal rubbed off on C# might be a stretch, but the influence of Anders Hejlsberg is undeniable in either language. I’m not really a huge fan of the OOP nature of the language for game development, but, I also don’t really have to concern myself with it too much. You see, Unity has already been optimized to be capable of some very high-fidelity and high-performance results within its own code base, it’s taken care of, so if I consider C# as merely the “scripting language” that I’ll use, as is the intention for the Unity engine, then it’s not too high a cost. Better yet, the high fidelity capabilities of Unity aren’t a barrier as they might be in Unreal, because Unity supports a gradient of graphical capabilities and a “Universal Render Pipeline” – A pipeline designed to scale from limited mobile or hand-held devices, through to high end PC’s.

The Unity Controversy

There was some controversy in recent years with Unity as a company. There was a fiasco involving the introduction of a runtime royalty fee, the back-dated changing of terms of use, and what the community described as a “trust me bro” attitude from the company with regards to this royalty fee. For the most part, as I’ll explain in a moment, these issues have all gone away since, but I’d first like to take a moment to explain my own experience with this.

I’ve been watching Unity for a long time, since its first version perhaps, or a very early version at least. The company grew incredibly quickly, winning accolades for its fast growth actually for several years running. Why? Well, at that early time it really was living up to the company promise of “Democratizing game development.” It was a company that made a game engine available for free, with very light restriction on its use for commercial purposes, and a fair, perpetual licensing model. As years went on however, it became obvious that the company was hungry for money. They rolled out a subscription model, and had a somewhat aggressive lock-in mentality towards it. I was already put off by this, but it seemed that they rolled this way for a decade or so. Unfortunately, they used that same time doing what I think was a mistake – they chased the Unreal engine. It looked as though they wanted to compete in the super-high fidelity market with Unreal, to cash in on the high-end corporate clients, and they did so to the detriment of the smaller studios and indie developers that they’d targeted with their earlier “democratizing” mission statement.

When Unity rolled out the questionable royalty fee, and back dated their terms of service (which may even be questionable legally), it hurt them. The community felt truly disenfranchised and began leaving the engine for GoDot (open source). Unity’s stock price took a nose dive, and the “bloggosphere” began scathing retaliations. Small to medium game studios gifted huge amounts of money to GoDot in an attempt to promote its development as an alternative to Unity.

Unity responded by replacing their CEO and as I understand it, many of their C-level staff. The new CEO (Matthew Bromber) came in during May 2024, and immediately reversed out the royalty fee requirement, and then simplified their licensing model. Matt (Matthew) has made public statements that he has done so to be more developer-friendly, in efforts to rebuild trust in the company. I think that this is the right move. If it works, still remains to be seen. A year later, their market still hasn’t fully recovered, and this is understandable. Trust takes time to build but can be destroyed in an instant. I don’t envy what Matt has to do in restoring the market – but – Unity is still a very strong product and today, is a viable option again for small and indie studios.

The Solution

Having decided to shelve my own game engine project and run with Unity, my decision making process has been lightened significantly. As I explained at the start of this post, some of my skill set (such as the programming) is already up to the task, but other parts of my skillset are behind. Creating artwork for example, I’m not strong at. I have some basic skills using Moho Animation Studio (a product I would recommend to anyone with a use for it), for 2D vector graphics creation and animation. I also have the basic fundamental skills with blender. My problem is that I’m no artist essentially. While I have skills with those two products, they are at a fundamental level, not a high proficiency, and so as I study the process of creating usable game artwork, I do so in programs that remain at least a little unfamiliar.

So how exactly did making the engine decision make my decision making easier? Well now, I know where to spend my time! I no longer have to worry about writing a video game engine or a tool chain, I have an engine that I can use, and I know more or less how to work with its tool chain. While I don’t claim to “know unity” in terms of the available code, classes, etc, I know that I can read manuals or tutorials and easily understand what is being done. While I don’t write C# often, I know it well enough that I can consult the internet when I forget how something is done, and I’ll get up to speed quickly. I don’t need to concern myself with cross-platform concerns (mostly), I know that the engine is capable of it. I can dump all of the slow-grind components of building up a game, and just script what I need when I need it… and of course, I’ll follow some tutorials to get up to speed. Instead, I can practice my artistic skills, which are not only in need of the practice, but, offer far more short-term rewards. I will no longer have to settle for being proud of having put a rainbow plane up on the screen, instead, I can be proud that I made a 3D dancing character and got that into a game project.

Given my limited skills, I decided to go with a “Low Poly” aesthetic and began following tutorials to create low-poly assets and characters using Blender. I don’t really have a game concept in mind for them yet, these are just practice projects essentially, but I’m already making some amount of progress…

These low-poly models made thanks to the free tutorial from Crashsune Academy / Love-chan : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Use9T2IX1XE&list=PLcaQc6eQjXCxWXmn5jxE_GTOft9ZxChu1

With special thanks to Grant Abbitt (https://www.youtube.com/@grabbitt) who’s tutorials on GameDev.tv got me up to speed with the blender basics necessary to begin the above tutorial series.

So, I can now make very “beginner” level low-poly characters and animate them.

Getting my own engine to the stage that it could run these animations would probably be another 6 months of effort!

I never thought I’d say this, but now I’m on track to become an Indie game developer using Unity.