It’s been three and a half months since I posted Episode 1 of this blog, which I’d intended to post to far more regularly.

What happened?

At the end of Episode 1, I closed with a sentence which at the time I believed to be true. It turns out that I was still lying to myself…

“I never thought I’d say this, but now I’m on track to become an Indie game developer using Unity.”

I write this post with a title about kicking an addiction, not to be taken literally, and not to belittle anyone with a genuine addiction, but because the pattern of behavior that I’ve exhibited has shown some similarities. It’s expressive intent only. The beginning of this post is essentially self-reflection, and the later portion will explain what little progress I have actually made. If you’d prefer to follow progress only, without my meandering, feel free to skip to the heading “Where I’m at now.”

The Addiction

I have been writing code professionally for (quick math) 26 years now, specializing in Delphi (Pascal), which I’d previously used as a hobby programming language for around three years. So, almost 30 years writing Pascal code, both professionally and for my own entertainment. Perhaps it has been a few years longer, given some vagueness in my memory. Prior to that, as a child I wrote code in BASIC and Assembler for various “toy” computers. Programming became a part of who I am, a component of my identity. Having done it for such a long time, I am still of the era in which every component of a software application could be, and often was, written from scratch.

I fell into the habit of taking on personal projects of ever-increasing complexity, only to be consumed by them, oblivious to the time passing by. Literally, weeks, months, or years could be swallowed by a project, and ultimately, they were always “never finished” projects. What happened between my previous Episode 1 blog post and this one, was precisely that.

After declaring that I was now going to focus on the game development, switch into Unity, and learn Blender more effectively, I instead went right back to working on my own compiler, and my own “game engine” projects. This is why I liken it to an addiction. In some ways, it is akin to one. I’m coming clean about having wasted another three and a half months of my life on efforts that I’d sworn to abandon, at least temporarily. I own up now, transparently admitting some shame.

I explained in earlier posts that not only do I want to make games, but I also want to share this passion with my young son. Getting swallowed up by my prior projects again put me back into a text console for long periods. I was not sharing the passion with anyone. I was hyper-focusing on my own pride-driven goals. I don’t know if anyone is reading this blog as of yet, but if so, then I’ve let you readers down too.

Pride and Programming

In earlier years, there was a sort of bravado in hobbyist programming. There was a period when many developers wrote what we referred to as “Demos” for the so called “Demo Scene.” The scene still exists today, as developers of the same ilk continue to write demos merely to keep it alive. The Demo Scene grew out of software piracy, because the pirates wrote demos to show off their programming prowess, after “cracking” copy protection. I won’t dive too deeply into that history, but suffice to say that the Demo Scene became its own thing, in its own right. Though a small shadow of its former self, it’s still alive today. Realistically the Demo Scene faded 30 years ago, but had been going strong for a decade or more before that.

In the 80’s and early 90’s, computer hardware was understandably far more limited than it is today. As a child I once owned a Commodore 64, an 8-bit microcomputer with a mixed purpose. It was leading-edge in terms of personal computing for its time, and also had business aspirations as demonstrated by its awkward sibling, the Commodore SX-64. The SX-64 was essentially the same machine as the Commodore 64, but packaged in a portable (laughably heavy) case, and was aimed at business users. The business computing industry faced a problem however, that there were too few programmers, and so both the SX-64 and the Commodore 64 shipped with a BASIC interpreter, manuals teaching how to code. The idea being not only that the business users be able to produce custom programs, but that children using the C64 would learn to code, and grow up to be software developers.

The Commodore 64 was named not because it had a 64-bit data bus, far from it, but because it had 64KB of RAM. Kilobytes. It ran at around 1Mhz (PAL or NTSC dependent) and could execute roughly 250 thousand instructions per second. By comparison, modern Intel CPUs approach 4 Billion instructions per second. Graphically, it could display 320×200 pixels in high-resolution black and white, or 160×200 in low-resolution color, unlocking a palette of 16 predefined colors, which also had strict limitations on how many could appear in any display region at once.

Nevertheless, I devised a special effect that appeared to add additional colors beyond what the hardware provided. I claimed in essence that I could make a machine that was limited to 16 colors display a 17th color. This is a claim that clearly deserves qualification. I didn’t actually create a 17th color for the C64. Instead, I wrote a small piece of Assembler code that rapidly swapped between white and yellow, fast enough that via persistence of vision, they blended into a shimmering gold. I vaguely recall reading about the exact same effect being used in a commercial game at the time, though I never saw that game firsthand. It’s entirely plausible that multiple developers independently discovered the same trick, given that we were all trying to push hardware beyond its apparent limits.

Techniques like color palette switching were at the heart of the Demo Scene. It was a creative playground where individuals or groups tried to one-up each other on modest hardware. One famous example is the “9-sprite” trick on the C64, which allowed nine sprites on hardware designed for only eight. One of my favorite examples comes not from a Demo but from a commercial video game: Elite (1984) by David Braben and Ian Bell.

Elite was written for the BBC Micro and was essentially an open-world space flight game. Braben wanted high-resolution two color mode for crisp star fields and wire frame ships, but that would have left the game colorless. His solution was to detect the vertical scan position and switch video modes about three quarters down the screen, yielding a colorful UI while retaining high-resolution graphics above.

(Aside: David Braben is a personal programming hero of mine. Beyond Elite, he created Frontier: Elite II and, decades later, Elite Dangerous. He didn’t just do clever video tricks, he also delivered a procedurally generated open galaxy on an 8-bit computer, pioneering what we now call open-world game play. Elite fit into only 22 KB. An engineering masterpiece.)

Programmers of those early times, earned a significant amount of pride in being the first to discover new ways to push the hardware limits, and to produce new effects that had not yet been seen, or even considered possible on the available hardware. I think my pride in taking on larger personal hobby projects, comes from having grown up and become a programmer through this earlier time.

Programming Heroes

Despite my efforts over the years, I never learned to ski. My wife, by contrast, is an accomplished skier with medals from local competitions. Through some twist of fate, she married a man who doesn’t ski, while I married a woman who doesn’t code.

Often, when explaining technology to her, I resort to sporting analogies. Once, during a long drive home, she asked: “In extreme sports we have heroes. Do you have that in programming?”

Of course we do. From Alan Turing, Grace Hopper, Niklaus Wirth, and Bjarne Stroustrup, to John Carmack, David Braben, and Tim Sweeney. Programming has its heroes, not because they mastered known techniques, but because they invented new ones.

The greatest painters aren’t revered because no one can copy them, many can. They’re revered because they created techniques and styles that didn’t exist before. The same is true in programming. John Carmack’s DOOM rendering techniques are well understood today. I even re-implemented them myself in the late 90s. What makes him a hero is that he invented them, and shipped.

This realization ties back to my struggle. Pride, competition, and identity pushed me back toward building my own engine instead of aiming towards finishing games. Even the expectations of peers within the Pascal community played a role.

The Real Reason

While pride and competition are factors, they aren’t the whole story.

The rest is simply comfort.

Pascal is familiar. Its syntax, compilers, editors, they’re my comfortable old slippers. Unity, Blender, C#, even Visual Studio are unfamiliar, and that makes me feel like a beginner.

Falling back into Pascal soothes that discomfort. But it’s also a sinkhole. Writing a game engine is already a massive time investment. Writing one in Pascal, with fewer off-the-shelf libraries, increases that cost.

“If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” — Carl Sagan

Looking back, it’s hard not to feel that a great deal of time slipped by without moving me meaningfully closer to my goals, and that realization has made it clear that something needs to change. At this point, the habit no longer serves my goals. I need to kick it.

Where I’m at now

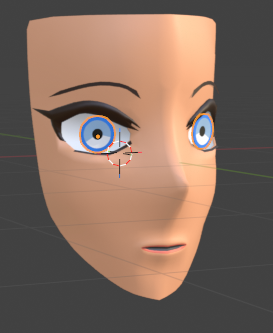

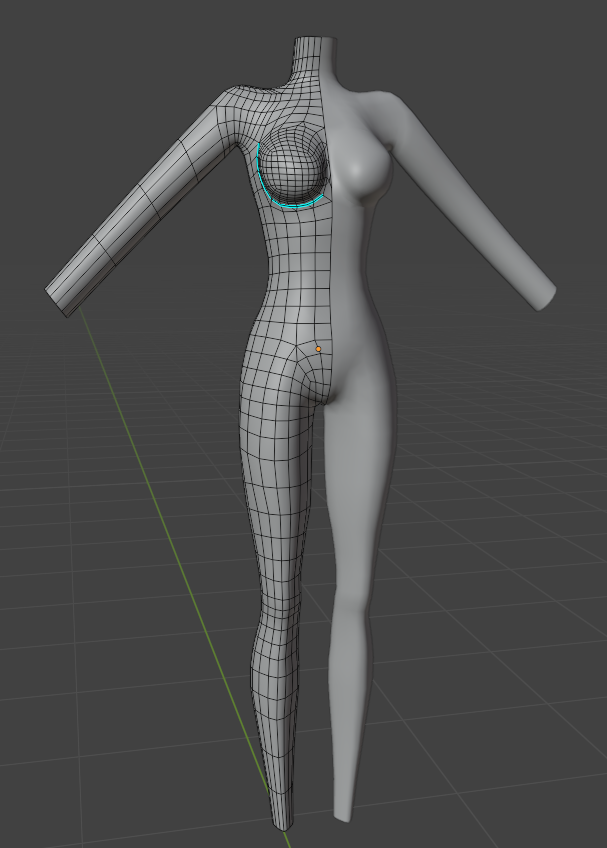

At the end of Episode 1, I showed some low-poly Blender models. Not good art, but progress.

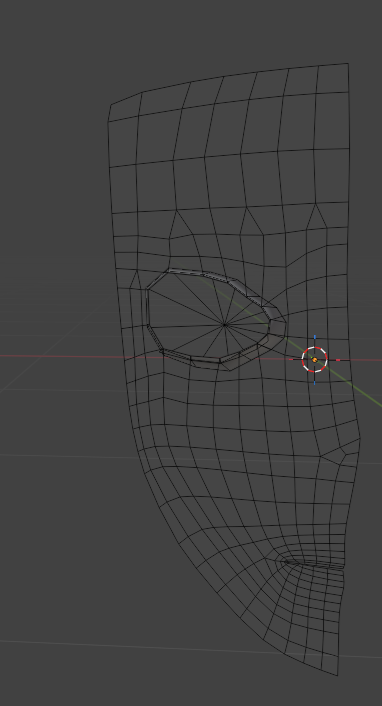

I’m now modeling mid-poly characters. Still not “good,” but intentionally so.

These new models I think are a significant step up from my earlier low-poly efforts, but they are somewhat out of proportion and crude.

What is important about them however, is that they have clean topology, designed for deformation during rigging and animation.

I’m targeting a polygon budget of 11-12k for a complete character model. With proper texturing and clothing, I believe the lack of detail can be masked effectively. These are already, I think, sufficient to serve as base meshes from which many characters can be created. I’ll need to alter the proportions of each, in the direction of some character reference, in order to achieve a final model, but then I can re-use these same base meshes again and again, to create further derived characters.

I’m intentionally avoiding the traditional high-poly sculpt, then retopology workflow.

While that approach yields realism, it’s extremely time-consuming. Instead, I’m embracing stylized assets that can be rigged once and reused many times.

These models were created by following tutorials from the YouTube channel “@2amgoodnight” https://www.youtube.com/@2amgoodnight – The presenter of which, I do not know the name of. The title “Genshin Impact” from “HoYoverse” is a video game that I know next to nothing about, however, the developers of it at some point released the 3D assets for download – I think in order to allow players and fans to 3D print them. The presenter of “2AM” inspected and reverse engineered these models, learning how they were made, and how to reproduce them using Blender. He then crafted tutorials out of this study. He also hosts a patreon account where assistive assets are provided too, and so I surely became a member.

Now, my models aren’t quite so good even as the tutorial results, I am still very much the student. The tutorials are also anime-focused, not my end goal, but they provide a usable foundation, without heavy sculpting or retopology. That time savings matters. They are perfect for my goals.

So, this is where I am. Closer to the end of another year, and barely any closer to having created anything that would count as a video game. I’m also not aiming at this point for my “magnum opus” or anything like that. I know that I’ll want to experiment with small toy games for the sake of learning the features of the Unity engine, and, I’ll want to create many more assets like the above, to practice and hone my blender skills. The truth is however that I leave you with essentially the very same revelation that I did at the end of Episode 1.

I am now (back) on track to become an Indie game developer using Unity.

For those of you that would not be bored by time-lapses, here’s the product of my efforts thus far, in video form…